Charting a Course for the Future

Having spent the past decade in the support of higher education faculty, I have had an opportunity to observe the evolution of the faculty development ecosystem. Increasingly, institutions are recognizing the value of providing centralized and systematic faculty development support services, programs and workshops. Providing this level of support for faculty seems to be at an all-time high with studies and reports from practitioners in the field confirming the need for such efforts and administrators giving priority on those initiatives.

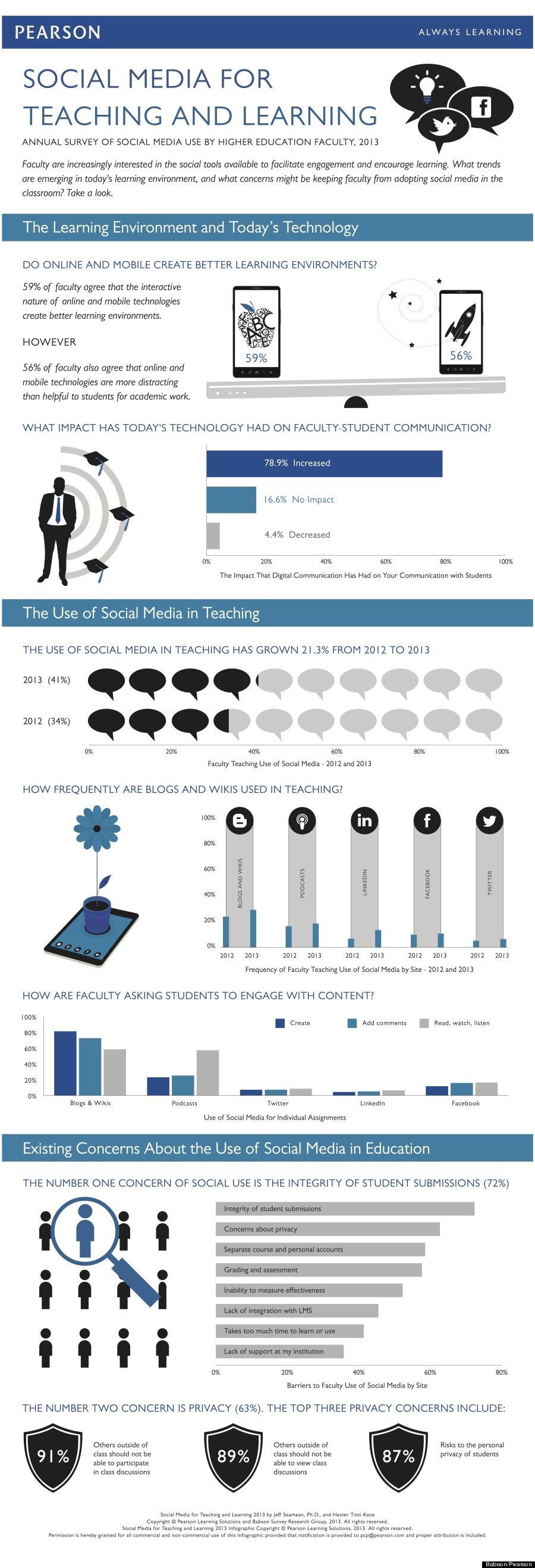

In addition to the faculty development programs at their home institutions, there are also more opportunities to participate in a wide range of workshops, webinars, and open courses through other organizations and institutions. The rapid growth of virtual attendance options for faculty, combined with the sheer volume of information and resources available online have resulted in a large selection of programs from which to chose. Faculty are also developing professional learning networks and leveraging social media where they can share their own tips, recommendations and best practices.

As new technologies and pedagogical approaches are continually perfected, there are no shortages of opportunities for experimentation and innovation in today’s college classrooms, both physical and virtual. It is easier than ever for faculty to select a new technology tool or instructional methodology and incorporate it into their teaching repertoire. Adaptations of “traditional” teaching methods in physical and virtual classrooms are just a few of the many forces converging to bring about a significant transformation of higher education in both the short and long term.

Despite all that has changed in the field, many constants remain. Faculty requiring assistance still seek out personalized support and appreciate having someone they can call or email for a prompt response. Many needs are localized to specific technology or academic system configurations making support provided by the institution critical. As we adopt new systems and processes for meeting evolving student requirements, faculty training on new features and workflows are necessary for envisioned outcomes to become fully realized. Institutions must also continue to serve faculty at varying stages in their academic career, from junior to mid-career to senior faculty status. Furthermore, tracking completion of professional development programs and expressed support continues to provide important data points that can inform both administrators and support staff on the progress made and challenges still to be met.

As I look to the future of higher education faculty development, I see several trends that I believe will persist in the coming years:

1. More ‘Just-In-Time’ Training and Resources

As technology for easily creating and sharing information and learning artifacts becomes even more commonplace, the number of training aids and resources will continue to grow. Faculty are becoming quite comfortable searching online for quick answers to technical and/or pedagogical questions as they arise and likely will not wait for a formalized training session. Educators are seeking training materials and resources made available in bite-sized pieces; easy to find and readily at hand.

2. Curation of Available Professional Development Resources

As the vast number of resources expand, so will the necessity for curating and help options that highlight the most applicable and relevant needs for a given scenario. While we are beginning to see the use of bookmarking and other social sharing tools with surface resources that a mass of users have viewed, liked, etc., there is room for continued tool improvement and systems to augment manual curation approaches. I envision an Amazon-style recommendation paradigm to become commonplace; where after accessing a resource, faculty are advised on other helpful alternatives. In the meantime, collections of links, tutorials, and other resources curated by faculty development staff will continue to be sought.

3. Flexible Participation Options for Live Programs and Workshops

With workloads continuing to increase for a growing number of part-time and adjunct faculty in face-to-face and online programs, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for a large number of faculty to attend live programs and workshops. Flexible participation options for live programs and workshops will go on to flourish and may cover a wide range of possibilities: such as live/online simulcast workshops and archiving programs for on demand access.

4. Recognition of Prior Learning

Given the availability of resources and a move toward credentialing prior learning experiences, faculty will continue to seek credentialing and reporting of their professional development activities for career advancement. This emphasis toward recognition will likely involve badges and other digital certification, but will certainly rely on institutions embracing faculty development initiatives completed while at other institutions, or through alternate organizations like the Sloan Consortium. It will be up to institutions to decide how they will accept and recognize certifications and trainings procured through other establishments while simultaneously ensuring that faculty possess skills deemed necessary.

5. Data-Driven Decision-Making

As it becomes easier to gather a wide range of data on faculty development outcomes, ever-increasing opportunities exist for this information to be used in guiding future offerings. As data is purposefully collected and analyzed, resulting trends can provide valuable insight into the utility of offerings and inform future decisions on prioritization of finite efforts and resources.

6. Renewed Focus on Mission and Offering Programming and Services to Meet Stated

Higher education is facing a time of unprecedented change and those leading faculty development initiatives will be well-served to sharpen their focus on their mission and offer programs and services to meet designated objectives. Initiatives that once met stated needs or requirements may need to be revamped, renewed, or perhaps in some cases discarded so that available resources can be best utilized.

Looking Ahead

What trends would you add to this list? What will shape the future of faculty development? Leave a comment and join the conversation!

Orignally posted 2/4/2014 on Sloan Consortium blog